Brookfield Zoo helps repopulate wolf species

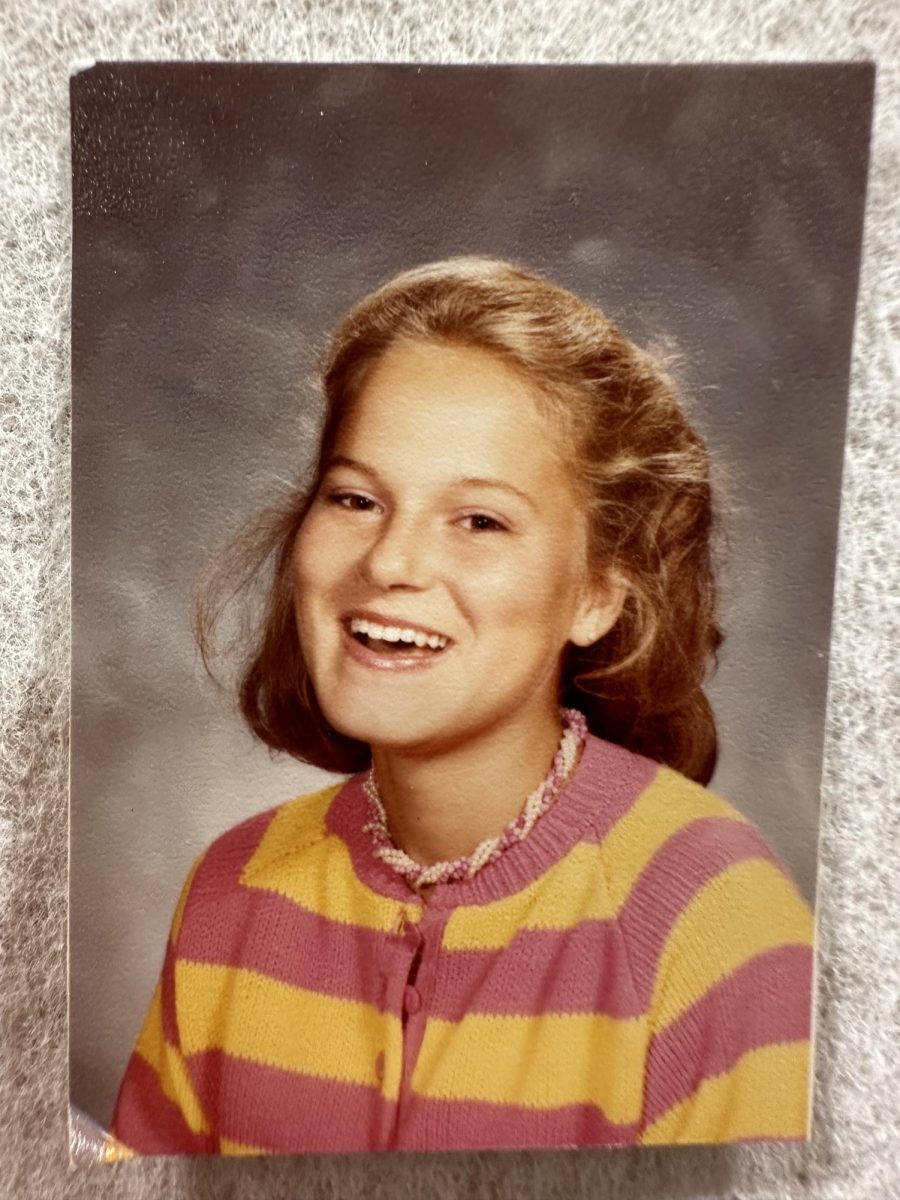

Apache (background) and Ela play in the snow and get acquainted at Brookfield Zoo. They can be seen at the zoo’s Regenstein Wolf Woods habitat (Jim Schulz/ Chicago Zoological Society).

March 1, 2019

Animals are moved in and out of zoos frequently, but the recent addition of Apache, a Mexican gray wolf, to the Brookfield zoo is more meaningful than bringing in a new inhabitant. This past December, a wolf called Apache arrived from Albuquerque N.M., the wolf was brought in as part of a species survival program.

In 1976, there were just seven Mexican gray wolves left in the wild. The species was on the brink of extinction, and in the face of poaching, loss of habitat, and an increased human population, their odds looked slim. American and Mexican wildlife foundations called attention to the crisis, and in 2003 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service started collaborating with zoos and animal rehabilitation centers to assist in repopulating the species. The Brookfield Zoo has been partnered with the Chicago Zoological Society (CZS) for many years, and has been involved with Mexican gray wolves since 2003. Because of USFWS’s commitment to repopulating the species, 145 wolves live in the wild, and 281 reside in captivity.

“[The Mexican gray wolf species survival] program is such an exciting program to be part of, ” said Joan Daniels, curator of mammals with (CZS), and Brookfield Zoo employee for 33 years. “We just love those puppies, and watching the mother and father [care for the puppies] is incredible.”

Daniels oversees mammal care at the zoo. She also ensures the zoo brings in new animals and moves some of them to different zoos, organizes their medical, nutritional and behavioral husbandry, and works outside of the zoo as well in species survival programs, she said.

“The Mexican wolf program is one of the most successful programs,” Daniels said. “We’re constantly being asked to do new things, liek hosting the international meeting with all our colleagues from Mexico.”

The wolf pack at Brookfield Zoo has recently been separated, according to the CZS. There were nine wolves housed at Brookfield Zoo, in two separate litters, or families. Space was tight, and the wolves were reaching the point of development where had they been living in the wild they would have split off from their family and started to form their own pack.

Nine of the 10 wolves have been moved to new locations, according to the Zoo- one alpha female remained, Ela. A new alpha male, Apache, has been brought in because the two are a strong genetic match and will hopefully produce offspring in the spring. Apache was found through a genetic match program, Daniels said.

Keeping track of the genetics is extremely important- when species numbers dwindle, the genetic pool shrinks and if repopulation is not carefully planned, inter-breeding two wolves with similar genomes may do more harm than good in the long run.

“Genetic diversity is probably the biggest scientific challenge we have,” said Maggie Dwire, assistant coordinator for the USFWS Mexican Wolf Recovery Program in an interview with WTTW. “When they were first brought into captivity they were managed in three different lineages.”

Those lineages are still being kept track of today, said Daniels, though it has expanded greatly. Databases compare the genomes of wolves in rehabilitation locations and zoos across all of North America, and the wolves are shifted around frequently to produce the best litters and results, Daniels said.

“Our biggest goal for our wolves is a nice sized litter,” Daniels said. “We want them to reproduce. [The zoo is] slated to do some cross-fostering of puppies [between] our animals and animals in the wild.”

Because Apache and Ela are a strong genetic match, their offspring will be genetically sound and may either be released in the wild or used to breed a new generation of wolves.

Despite the careful management, the wolves are still left to much of their own devices, Daniels said.

“They’re wild animals,” she said. “Ela has constructed nest sites and den sites, and then we let them build their own den sites and nests if they want.”

The average mating season for Mexican gray wolves in early March, with a 63-day gestation period. It is not yet known if she will conceive this year, as Apache was only moved to the zoo in December, but hopes are high that a new wolf litter will be born in spring.

“Apache and Ela have been good and compatible and playful with each other,” Daniels said. “It took a while to sleep near each other, but now they snuggle up together. Neither have reproduced before either, so it would be a first litter for both of them.”

Each wolf may only have three litters, in order to maintain an even genetic pool, she said. After their breeding years are over, they may be moved to another facility or kept in Brookfield, as many patrons have grown attached to the animals and are invested in them, Daniels said.

“[The zoo] has been an incredible opportunity,” Daniels said, speaking for not just herself and the community, but for the dozens of species the zoo has helped repopulate. “It keeps getting better all the time- the direction is just incredible.”

![Movie poster for [Rec] (2007).](https://www.lionnewspaper.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/rec-640x900.jpg)