Media Mayhem: What even is a news organization?

It can be very easy to think of a newspaper as a manufactured product like your soaps and your silverware. But a newspaper is more than just that.

March 5, 2019

It can be very easy to think of a newspaper as a manufactured product like your soaps and your silverware. If you look at the way you get your soap and silverware and the way you get a newspaper, they can look somewhat similar.

Heavy machinery in a warehouse somewhere transforms a normal piece of metal into a spoon you can use to eat your soup with. Similarly, heavy machinery in a warehouse somewhere turns an empty piece of paper into a newspaper with words and photos and bylines that you can then go about reading. Now you just have to buy it.

People buy their newspapers either at a newsstand or in a yearly subscription—people hand-over their hard-earned dollars and cents and in return they receive pieces of papers with words and images printed on it—but that is a gross simplification of the real work of a newspaper, or any news organization for that matter.

Most people don’t buy their soaps in subscription format, but at most you need more soap once a month. But the news is in constant fluctuation, things are always happening, so to be able to stay on top if it, you need a lot of newspapers.

But, if you think about it, the physical paper on which articles and photos are printed is not worth $3 at your local Starbucks or around $700 a year for an annual subscription. Those numbers are not made up. That $700 figure is the price of an annual subscription to the New York Times, according to Slate.

At the end of the day, the 700,000 people who are forking over $700 a year for The New York Times are not paying that amount of money for the physical paper: they are paying $700 for the world-class journalism that the New York Times produces.

That is why I have a tough time thinking of the New York Times and other newspapers as a manufactured product, because the New York Times can look really pretty, but is a pretty piece of paper you retain for a day and then throw into the recycling worth $700?

Ultimately, it is all about the role the New York Times plays in people’s lives—the trust people put in the New York Times to provide the important information a person needs to go about their lives and have a firm grasp on what is going on in Washington and across the world. That’s why people pay $700 a year for the New York Times, not the paper itself.

With that in mind, if a newspaper looks real pretty but the information inside of it is not worth reading, why would someone buy that? If a newspaper gets caught in a systematic scandal of fabrication, a person then starts to wonder, “Is this a product worth spending my hard earned money on? Am I getting my money’s worth?”

The newspaper is a product, but it is not the product that a newspaper and other organizations need to succeed. At the end of the day, the product news organizations create is trust. The trust of their readers translates into subscriptions and sales at your Starbucks newsstands, but in the absence of trust a newspaper is just a piece of paper.

This is why the erosion of newsrooms across America concern me.

As the corporate entities strip resources out of institutions like the Denver Post—which has seen its staff shrink from a staff with more than 250 talented journalists to one with fewer than 100—it doesn’t just translate into lost jobs: it translates into lost value.

A person paying money for their news will only tolerate a certain number of bad articles before they cancel their subscriptions. Once a certain number of customers cancel their subscriptions, that only leads to more lost jobs.

In the manufacturing of spoons, you can find ways to streamline your production. You can find ways to make the production cheaper. If it looks like it spoon, if it works like a spoon, it’s a spoon. But in the manufacturing of the news—if you cut enough corners—it may still look like a newspaper, but is it one that is worth paying for?

Oftentimes, the answer is no.

Many newspapers in America are still profitable, but yet we’re still seeing the newspapers making major cuts to their newsroom staff? Why? Well, when I heard journalist Celeste Headlee speak at Mercer University in February, she asserted that the corporate interests want a fatter bottom line. They want more profit, and they think cutting jobs can boost profitability.

But after a while, those job losses mean lost subscribers. When we lose subscribers, we lose even more local news. That should concern everyone.

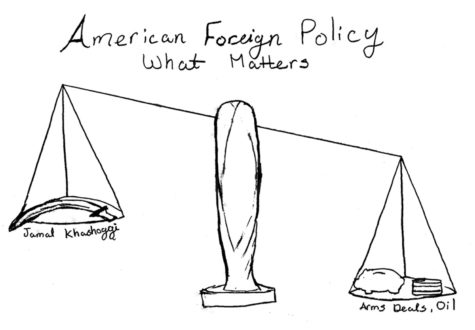

Without our local newsrooms, local politics will only get more corrupt than it already is. With the scandals swirling around Chicago Ald. Ed Burke, local politicians know that there are news organizations with their eyes-open for corrupt politicians. Without that community watchdog, imagine how many more Ed Burkes would go unaccountable?

![Movie poster for [Rec] (2007).](https://www.lionnewspaper.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/rec-640x900.jpg)