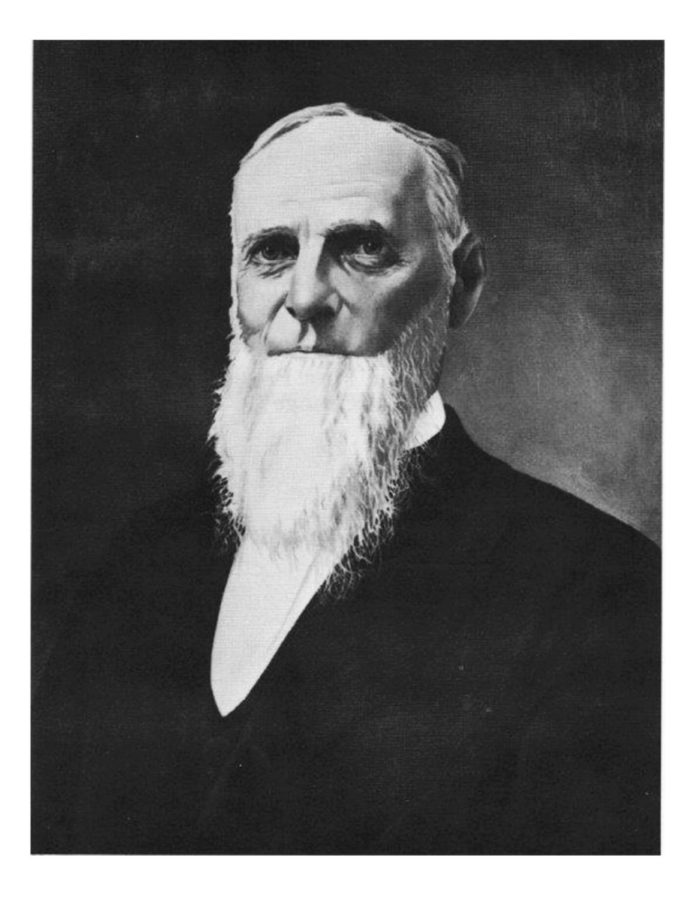

La Grange founder owned slaves

Franklin Cossitt, founder of La Grange, first a cotton planter in Tennessee

April 30, 2018

Up until the mid-1950s, the majority of the people living in La Grange could not consume alcohol in the confines of their own home—they risked having their house confiscated if they did. Franklin Cossitt, the founder of La Grange, had seen too many towns emerge around the pub and the bottle. This wasn’t how he wanted La Grange to become.

But more than that, Cossitt was a man who overcame in the face of adversity, relatives say.

“He lived through some horrible times and yet he kept going—he pulled himself up and kept moving,” Nancy Kenney, a relative of Cossitt’s and a local historian, said. “He lost his home and his business in the Civil War, two of his wives died during childbirth but he just kept going.”

Kenney is an expert in La Grange history and Cossitt in particular, noting the many actions he made that have had positive, direct impacts on the La Grange of today.

“I think he was a visionary,” Kenney said. “He had this dream of developing land. He could see what was happening. The Burlington [Railroad] had a line out here so he purchased this land… and came and devoted himself to this full time.”

When building the town, Cossitt put emphasis on making La Grange a place where people would want to live. He allocated land for churches and schools, planted a plethora of trees and even offered to help early residents build their new La Grange homes.

Cossitt envisioned a town of culture and class, a town where the neighbors were nice, the houses were pretty and family and religion were a part of everyday life. He wanted a quality community, and he modeled it—in part—after a La Grange he knew well: La Grange, Tennessee.

The southern La Grange was home to two colleges, four churches, multiple newspapers, a hotel, a painter and numerous other businesses. The town also had cotton plantations and cotton farmers—which was Cossitt’s field of work.

The LION has confirmed through census records from 1860 that Cossitt owned at least 98 slaves in the county where La Grange, Tennessee, is located. In federal documents, it notes that Cossitt owned around 130 slaves across his four plantations.

Cossitt’s situation highlights a difficult and precarious conversation about how to reconcile the role many historical figures played in shaping the way our nation, our states and our communities emerged with the fact that many of these figures enslaved other people.

Community reaction

Kenney, the Cossitt relative and historian, speaks with immense pride regarding Cossitt’s accomplishments. She sees him as the embodiment of the American Dream.

When talking about Cossitt owning slaves, however, Kenney became visibly shaken, both for how it may change how people see his good work and the fact that he had played a role—however minor or significant—in this negative period of American History.

“I hope that people will not think too harshly of him,” Kenney said. “He engaged in an evil, but if the times were different, I think he wouldn’t have engaged in slavery.”

Other than the sheer act of owning slaves, Kenney notes that—to her knowledge—there is no evidence to suggest that Cossitt mistreated them, but there is also no documentation to backup that he treated his slaves well either.

Making the topic more difficult, the local elementary school in La Grange includes Cossitt’s name. The school is not named after Cossitt but rather the street on which it resides. The official name is the Cossitt Avenue Elementary School.

While no one has suggested changing the street’s name, if the street’s name does change, the school board would likely have to consider whether or not to change the school’s name too, said Kyle Schumacher, the superintendent of District 102, which oversees the school.

“I think it is an important distinction,” Schumacher said. “Our schools are all named after streets, and so there is a disconnect from the namesake.”

Schumacher said that having a school named after a person is intending to honor an individual. When a school is named after a street, that is not the case.

“If our school’s were named after people, [changing the name] would make sense,” Schumacher said. “Our school’s names are not honoring anyone.”

While very few schools have changed their names because of their namesake’s ownership of slaves, there is precedent. In the 1990s, after pressure from civil rights organizations, the school board in New Orleans changed the name of all of its schools named after slave owners, including an elementary school named after President George Washington.

While not calling explicitly for changing the name of Cossitt Elementary, President of LT’s Black and Multicultural Club Nina Shearrill ‘20 argues that one must look at how a historical figures’ slaves helped them get to their position of power.

“I feel that these people are being praised for things they did through terrible means,” Shearrill said. “The way that they got their power, the way that they got things done is off the backs of other people… Without the people that they enslaved, they wouldn’t have the legacy that they did.”

The sponsor of Black and Multicultural club, Elizabeth Watkins, declined to speak to Cossitt’s situation until she did her own comprehensive research on the subject.

But Paul Houston, Global Studies Division Chair at LT, said that—if it was his choice—he would use this as an opportunity to discuss the role of slaves in America and their role in the lives of historical figures.

“I think having a school named after a slave owner like Cossitt could be an educational opportunity,” Houston said.

He added: “If we were to include a brief instructional program in a U.S. history class about Cossitt, I would endorse examining the complicated biography of a man who did all these great things and could be revered but owned slaves,” Houston said. “That would help some people think about how the world is complex, and people are complex.”

Unlike the controversy surrounding the removing of statues depicting Confederate individuals, Kenney notes that Cossitt was, in fact, a Union sympathizer.

Cossitt in the South

According to local history books, Cossitt was born in 1821 in Granby, Connecticut. At 15 years old, he moved to Tennessee where he worked for his uncle, but then went off on his own and began cultivating cotton.

La Grange, Tennessee—located on a beautiful bluff overlooking an offshoot of the Mississippi River—proved to be quite an advantageous position during the Civil War because of its view into its southern neighbor: Mississippi. As a result, the Union occupied the town during the Civil War.

While he was not very outspoken on his beliefs, Cossitt was a Northern sympathizer.

Cossitt’s estate, The Taira, was used by the Union as a hospital and a biography written about Cossitt even claimed that he entertained Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his wife when they were in La Grange, Tennessee, for the war.

When the Union was encamped in the area, the town saw much of its business and culture vanish, the current owners of Cossitt’s La Grange, Tennessee, estate, the Taira, said.

As a result of the Union’s impact on Southern property, between 1871 and 1873, the United States offered Northern sympathizers the opportunity to receive compensation for property that was taken or destroyed by the Union during the war. Cossitt was one of them.

“Cossitt has rendered good services at different times [to the Union] and deserves compensation for [the] articles taken from him,” Union Gen. James McPherson said in the court report.

Before the union took La Grange, Cossitt came to McPherson’s and Grant’s encampment in 1862 and informed them that the Confederate troops in La Grange, Tennessee, “did not amount to much and [they] would have no difficulty in” taking the town, the report said. McPherson and his troops came in the next day and took La Grange from the Confederates.

Another Union general quoted in the report—obtained by the LION through the La Grange Historical Society—called Cossitt “a reliable Union man” and added that “I have reason to believe that he has always been loyal to the government and [I] have received from him valuable information.”

Some community members, including his relative Kenney, think this as a sign that Cossitt—even being a slave owner—had a conscious.

“The very fact that he risked his life [to help the Union], the fact that he freed his slaves are things I hope that people will [take into account and] understand,” Kenney said.

The LION could not independently verify whether or not Cossitt freed his slaves. In court documents, however, a Union general was quoted as saying that Cossitt’s “life would not have been worth a straw outside of the range covered by the U.S. Troops.”

Other La Grange, Illinois, residents agree that there is evidence that—while not exonerating him—helps to protect his legacy.

“There were no good slave owners, but there is a level of relativity,” La Grange, Illinois, resident Matthew Scotty said. “If he recognized the errors of his ways and changed his behavior, that is a positive mark on his character. It doesn’t excuse former bad behavior, but it is better than staying in the South and fighting for the Confederacy.”

Other locals say that, because there does not appear to be a direct link between La Grange and Cossitt’s slaves, it is less important to La Grange history.

While some of Cossitt’s actions reflect well on his character, others believe that those actions don’t make up for his ownership of slaves. Shearrill, the president of LT’s Black and Multicultural club, argues that Cossitt’s slaves certainly influenced his ability to build La Grange.

“There is always a connection [to a slave owner’s success and their slaves] because [that’s] how they made money and how they gained power: through what they owned,” Shearrill said. “If they hadn’t owned slaves, if they didn’t have the biggest plantations, they wouldn’t have been as prominent figures.”

![Movie poster for '[Rec]" (2007).](https://www.lionnewspaper.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/rec-640x900.jpg)

Deborah Bills • Jul 21, 2020 at 3:39 am

I’m interested in Lagrange Tn. History. My father John Bills was born in Lagrange Tn. In 1925. His father was Arthur Bills born there also in 1898. My Great grandmother Gertrude Bailey was born there in the 1860’s or. 1870’s. My great grandfather name was John Bills as well. Gertrudes dad was Richard Bailey and his father was Benjamin Bailey also born there. I would be grateful to rcv any info u could find. Thank you very much Sincerely Deborah Bills

Lily • May 5, 2018 at 12:38 pm

We love applauding and giving attention to old men who owned slaves and glorifying it around here ??

Lars Lonnroth • May 26, 2018 at 7:53 pm

I appreciate your feedback! I worked to give perspective to all parties in this issue. I just aimed to lay out the good he accomplished while also including the perspective of those who have the belief that his ownership of slaves merit him to be condemned in the history books. The fact of the matter, there has been minimal public discussion on this topic so my goal was to start a conversation on the role of slavery in La Gramge’s history. Would love to have greater dialogue on this. Please get in touch.